IT used to be easy to poke fun at Nicholas Negroponte. The founding director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Media Lab — and for many years the marquee columnist for Wired magazine, which he also helped found — Mr. Negroponte was one of those people given to pronouncements so grand they bordered on the grandiose. The Financial Times once described him as being "the world's chief cyberevangelist" who liked to prophesy that the Internet would "bring world peace, destroy trade barriers and promote democracy." His 1995 book, "Being Digital," cemented his reputation as the Bernard-Henri Lévy of the digerati: even when he was right, he made your eyes roll.

In the late 1990's, though, Mr. Negroponte began ratcheting down the pontificating. He gave up his Wired column in 1998, and in 2000 he stepped down as the head of the Media Lab, though he remained at M.I.T. And a year and a half ago, he took a leave from the university to do something you just don't expect from a 63-year-old man who has long made his living taking the 30,000-foot view. He decided to roll up his sleeves and create a new computer.

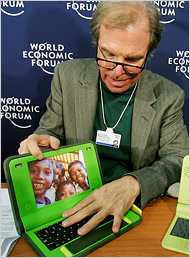

Not just any new computer, either. Mr. Negroponte and the 10 or so technologists who have joined him are trying to design — and mass-produce — a computer that will cost a mere $100, a price so low that governments in developing nations will buy them in bulk and turn them over to children who live even in the poorest, most remote areas of the Third World. Someday, he hopes, there will be hundreds of millions of such machines all over the world, revolutionizing the way children learn. And as poor children gain knowledge that has long been out of their reach, they will help raise living standards all over the world.

Right now, Mr. Negroponte's nonprofit organization, One Laptop per Child, is testing prototypes, raising money, and talking to governments. It plans to start in seven countries, at a million laptops a country. Advanced Micro Devices is building the microprocessor for the laptop, and Quanta Computer has agreed to manufacture it.

Mr. Negroponte expects the laptop to be in production by March 2007, with an initial price around $135 that will drop as low as $50 by 2010. Whether or not this is realistic, it is unarguable that what Mr. Negroponte is trying to do is both really hard and really good.

You'd think the world would be standing up and cheering. And in some quarters, that is happening. "It is an inspirational effort and a very important step to take," said Calestous Juma, who teaches international development at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard.

But not everybody is so complimentary. This time, though, those mocking Mr. Negroponte are among the most important people in technology. Bill Gates, for instance. When asked about the $100 laptop last month, the Microsoft chairman replied, "Geez, get a decent computer where you can actually read the text and you're not sitting there cranking the thing while you're trying to type." Craig R. Barrett, the chairman of Intel, called the machine a "$100 gadget." This month, Mr. Negroponte lashed back at a trade show in Boston.

Although everyone is now trying to lower the temperature, the dispute speaks to some serious, underlying issues. What does a computer need to be truly useful? What makes the most sense in terms of bringing computing and connectivity to poor areas of the world? And how can computers best help children learn?

Let's dispense first with the crassest part of the dispute. The operating system for the $100 laptop is a version of Linux, the free open-source software. And yes, Microsoft would prefer that it run Windows. "I think it would be useful to have Windows in it," acknowledged Craig Mundie, one of Microsoft's three chief technical officers. He argues that because Windows is installed in most of the world's computers, there is a Windows "ecosystem" that includes tens of millions of people who know how to operate Windows machines, fix them and use them as teaching tools. (Could it also be possible that Microsoft is worried that putting 100 million Linux machines into the world might pose a threat to the Windows hegemony? Mr. Mundie was not about to go there.)

Mr. Negroponte, though, can sound downright evangelical when he talks about open-source software. All the machine's software will be open source, not just the operating system, because Mr. Negroponte believes that people should be able to get into the software and make it better, and that can be done only with open-source code. And he is not just talking about professional developers either. "We believe that the kids ought to be able to go in there and do their own code," he said. Part of Mr. Negroponte's vision is that even illiterate children will be able to use the machine virtually the moment they take it out of the box — and that, in time, they will adapt it to their own needs and desires. The Microsoft/Intel view is that what Mr. Negroponte is proposing is implausible—that kids who have never dealt with computers simply won't have the skills to be able to do much with a computer without some professional training.

Which leads to the second area of dispute. Behind the $100 laptop are some radical theories of learning that have been championed by Seymour Papert, a former M.I.T. professor and a close colleague of Mr. Negroponte. Mr. Papert is a critic of modern curriculums, and a leading proponent of using computers to, in effect, learn by doing. "The computer," he told me, "is a way to make teaching less formal and abstract and more experiential."

On some level, the $100 laptop is a stalking horse for Mr. Papert's ideas. Maybe a village that gets 50 laptops will have a good teacher — but maybe it won't. In Mr. Papert's view, that shouldn't matter all that much. With the right software, he believes, the machine itself will help kids transcend the limitations of their teachers and their environment.

But that is a notion a lot of people have trouble accepting. "When you ask them who is going to create the programs for this, they say, 'the kids,' " said Michael Gartenberg, an analyst at Jupiter Research. "You ask them who is going to fix the machines. They say, 'the kids.' Who is going to create the curriculum? 'The kids.' Some of this stuff is going to need adult supervision."

The third element in dispute has to do with what a computer really needs to be useful. The $100 laptop will have a great deal of what we think of as a modern computer, including word processing, Wi-Fi and more. It will indeed have some sort of crank — or maybe a pedal — to generate power; how else can it work in places that lack electricity? It will have a dual screen that will allow children to use it either as an e-book device or a normal computer. It will be able to network with other $100 laptops, so that if a village lacks Internet access, at least the 50 or 100 kids can communicate with each other.

But it will not be "fully loaded" as we know that term today. The Microsoft/Intel argument is that even poor children want real computers that do everything traditional computers do. The One Laptop per Child team, however, takes the view that much of what exists in a computer is bloat. Mr. Papert became irate when I mentioned that Mr. Barrett of Intel had called the $100 laptop a gadget. "That's a joke," he said. "For most people in the world, it is a better computer than they are selling because it is not bogged down with all the junk they put in computers."

Modern computers also cost a lot more than $100, which is why the big computer makers have generally argued that it makes more sense to set up Internet kiosks, or computer cafes, where people can share machines. By contrast, Mr. Negroponte and Mr. Papert insist that for learning purposes at least, it is critically important for children to have machines that they own, and which they can use all the time.

I must say, I find this latter argument pretty persuasive. Or course, I don't live in the developing world — but then neither does anyone else arguing over these issues. And that is what ultimately makes this fight both so depressing and so silly. It turns out that there are lots of efforts under way right now to get computers and Internet connectivity to the poor regions of the world. Advanced Micro Devices has a program called 50x15 — it hopes to have 50 percent of the world connected to the Internet by 2015. Microsoft has a bunch of programs. So does Intel. Next week, at a big conference in Austin, the two companies, along with Dell, will introduce a new low-cost notebook device that the three companies hope will be suitable — and desirable—in the developing world.

But who knows if that will be the answer? And that is the real point. Nobody has a clue at this point what will work and what won't. Mr. Negroponte's effort is important because it is so different — it is not wedded to modern computing business infrastructure. Mr. Negroponte thinks that will be a huge advantage. But it could just as easily be a crippling disadvantage.

There is only one way to find out: make the machine, start handing them out and see what happens. For now, the only thing his critics should be telling Mr. Negroponte is "Good luck."